We tend to think of love as a good thing, regardless of the circumstances.

But I’m not sure Plato would have agreed.

Or at least, he might not call everything we label “love” by that name.

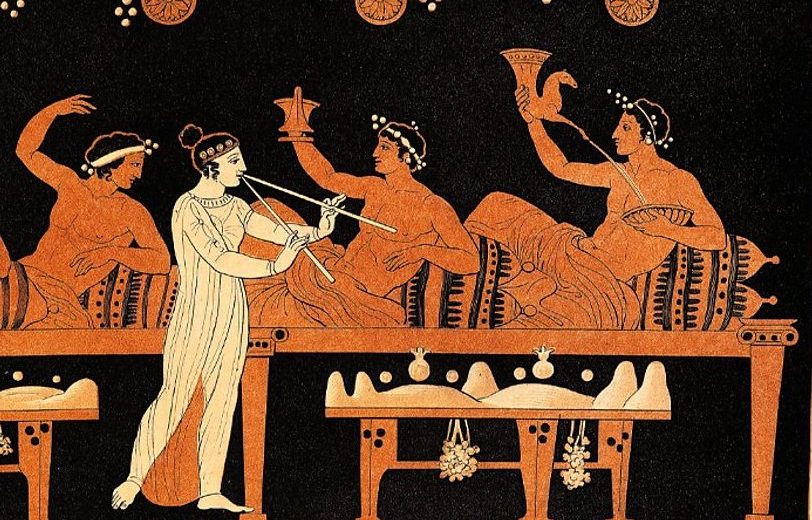

In his famous dialogue, The Symposium, Plato explores concepts of love through the mouths of seven famous Athenians. These guys are all at a dinner party, though they’ve agreed not to drink (because they’re all too hungover from their last dinner party).

One of the guys says, “Hey, we should all compose extemporaneous speeches in honor of Love [meaning Eros]! That’d be fun, huh?”

Because they’re Ancient Greeks, they all agree this would be a very good time indeed.

Can you imagine going to a party and someone is like, “Hey, let’s all put together presentations about the nature of love! Then we’ll judge whose was the best. The only rule is: no drinking.”

(Actually, as a sometimes-actor, I can see that being a good time. It’d be hilarious to see my friends make up on-the-spot songs or monologues about a given topic. Love! Hope! Hamsters! Wax poetic, everyone! It’d be hard to get them not to drink, though.)

The Symposium approaches love from an undeniably Ancient Greek perspective—where the love between older men and teenaged boys/young men was common and encouraged.

But there’s more to the Ancient Greek concept than that.

One of the speakers, Pausanius, says of Love:

“Love is, like everything else, complex: considered simply in itself, it is neither honorable nor a disgrace—its character depends entirely on the behavior it gives rise to.”

Consider those people who think they’re in “love,” but what they have is really an abusive bond.

Or they support each other’s victimhood instead of raising each other up.

Or they bring out the worst in each other—like Bonnie and Clyde.

Here’s another speaker from The Symposium, Phaedrus:

“If a man in love is found doing something shameful, or accepting shameful treatment because he is a coward and makes no defense, then nothing would give him more pain than being seen by the boy he loves—not even being seen by his father or his comrades.

“We see the same thing also in the boy he loves, that he is especially ashamed before his lover when he is caught in something shameful.”

According to Phaedrus, you’re only in love if you’re with someone who calls you to be the highest version of yourself. This is the noblest form of love.

You should admire your lover. You should respect them, and strive to earn their respect in turn.

Your love should urge you toward honesty and wisdom.

Love should compel you to practice moderation and treat others justly.

Love should inspire you to develop your God-given talents, and give you courage to stand up for your honor.

You should feel ashamed to behave ignobly around your lover—to be caught in drunkenness, thievery, gambling, cowardice, or just making a damn fool of yourself.

Now, I’m not saying I agree with these sentiments 100%.

Shame does have its purpose, and I definitely want to impress my lover. But if I fuck up—not an “Oops, I cheated on you!” fuckup, but more like an “Oops, I felt sad today and had too much to drink and danced like Shakira at Applebee’s!” type of fuckup—I’d want someone who would not look down on me for that.

But I fully agree that the person you love should call you to be the best version of yourself.

That aligns with a quote I keep close (and I wish I could remember who said it! If you know, drop a comment!) When you’re wondering whether someone is a good friend or lover for you, as yourself:

“Can this person help me be the best version of myself? Can I do the same for them?”

— quote by someone who I can’t remember. :-/

*

Love,

L.